With seven years experience as a museum educator and roughly the same amount of time before that as a mathematics teacher, I have an almost unique perspective from which to analyse the intersection between these two disciplines and this has been the driving force behind my decision to concentrate on the role of museums in mathematics education. De Freitas and Bentley (2012) say of museum-based integrated curricula that “students are afforded experiences that radically disrupt traditional philosophies of mathematics,” whilst Harrell and Kotecki (2015) assert that “authentic, in-person experiences with objects is crucial to make meaningful connections for students.” They also recognise that “experiences can be hindered due to geographical, financial, and time constraints of our audiences.” At my own museum and those of colleagues in similar roles elsewhere it is often also the case that these same constraints apply not just to audiences but to museums themselves. One response is to reach out beyond the confines of the physical museum space, and this can be done either in person or digitally. This assignment will concentrate on the latter, investigating the question;

What do Secondary School Mathematics Teachers want from digital museum resources?

|

| An Enigma machine and a laptop |

For the purposes of this assignment the phrase 'digital museum resource' refers to any digitally-served learning resource offered by a museum for use off-site and without direct involvement of museum staff. It is recognised that there are digital museum resources that fit the latter condition but require staff involvement (for example, webcasting and videoconferencing), but these are not included within the scope of this research. This definition is provided as, during the course of researching the theme it was evident that some of the teachers consulted parsed the phrase as 'resources supplied by digital museums' rather than 'digital resources supplied by traditional museums'.

There are not many digital resources offered by museums that focus specifically on mathematics. Some of the providers and resources considered whilst researching this assignment are linked in the embedded Padlet below. Most of the resources encountered were printable pdf files designed to be used as worksheets or planning materials.

Academic literature

Initial searches revealed that academic literature relating to this specific topic is similarly sparse, but there is plenty on component topics: the benefits of museum learning opportunities to schools (with reference to the development of websites and other digital provision) and the relevance of digital technologies in mathematics education are two that I have concentrated on. It is also important to note that while there is a wealth of writing on some of these intersecting themes, much of it is a few years old by now.

Museum learning and schools

Lin, Fernández and Gregor (2010) discuss website design with relation to informal learning in the museum context. They argue that enjoyment is a key aspect of online learning and identify characteristics of materials that may help to promote this: novelty; harmonization (i.e. coherence of design coupled with appropriate learning content); no time constraint; and proper facilitations and associations (including external links and extra information). They also put forward some guidelines which suggest that enjoyable online learning experiences are: multisensory; story-based; (positive) mood building; fun; and have opportunities to establish social interaction. As mentioned by Martin (2004), “museum learning may be said to straddle the ‘formal’ and ‘informal’,” so these characteristics and guidelines may well be used to inform the development of digital resources designed to complement more formal learning in schools. These ideas are also supported by a survey of teachers conducted for this assignment which will be discussed in more detail later. One issue which permeates all of this is the subjectiveness of terms such as ‘fun’.

Digital technologies and mathematics teaching

With regards to the use of digital technologies in the teaching of mathematics, Rowlett (2013) reminds us that “Educational technology may not produce a benefit simply by its introduction, but a benefit may derive from a change of approach driven by the use of the technology.” Further, The National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (NCTM) encourages “mathematics lessons that take advantage of technology-rich environments and the integration of digital tools in daily instruction” (Nelson, Christopher, & Mims (2009) and Pierce & Stacey (2010), cited in NCTM, 2015) and states as part of its official position that “when teachers use technology

strategically, they can provide greater access to mathematics for all students.” (NCTM, 2015, emphasis added). This supports some of the general guidelines discussed in the previous paragraph (but in the specific context of mathematics education) and also provides reassurance that museum resources that take advantage of digital technologies may find a welcome home in mathematics classrooms.

Digital skills

Also of interest is the comparative states of digital technology adoption and skillsets evident in the Education and Heritage sectors, which will almost certainly have a bearing upon both what can be produced by museum educators and what will be useful to school teachers. The Curriculum for Wales Digital Competence Framework is a comprehensive website detailing the digital skills that should be embedded at every stage in the Welsh school system. Its strands and elements are summarised as follows:

|

| Figure 1: Welsh Government (2018) |

This gives an idea of the kind of digital skills that should be embedded across all subjects in school curricula, and hence would not only be appropriate if embedded in digital resources offered by museums, but actively beneficial and desirable. Contrasted with this, though, there is a recognised deficit in digital skills in the museums sector (Parry et al. 2018, p. 1), with “Education and learning roles – creating interactive learning resources, delivering online resources and producing copies of objects for learning activities;” cited as a particular example of digital aspects growing in museum roles (Parry et al. 2018, p 18).

Teacher survey

But what do teachers want? In preparation for this assignment UK secondary school mathematics teachers were invited via Twitter to take part in a Google Drive survey which asked questions about their needs, hopes and experiences to date with regards to digital resources from museums. 113 usable responses were submitted and analysis and commentary of some of the data is given below.

Opinion of existing resources

Teachers were asked to provide some keywords that describe their general opinion of digital resources offered by museums to date. These were gathered as free text and the resulting words (and phrases) were sorted into categories under a theme, represented by a single word or short phrase. A word cloud was then generated, with larger text generally signifying more common themes:

|

| Figure 2: Survey respondents’ opinions of digital museum resources. |

By far the most common themes were those represented by the words “unknown”, “unaware”, “none” and “non-existent”, indicating that the maths teachers who took part in the survey were largely unaware that mathematics resources are offered by any museums. Of the people whose responses implied that they had come across such resources before, opinions were largely negative with a key theme being “irrelevant”. A handful of positive responses coupled with the relatively common “hard to find” and “never looked” may point towards the issue being exacerbated by lack of marketing rather than entirely down to such resources not existing. Conversations with a number individual teachers revealed inconsistencies regarding what constitutes a digital resource, which may also have affected the results. For example, a PDF lesson plan was considered by some to fit that description, but not by others.

The same process was used to generate a word cloud for the survey respondents’ ideal digital museum resources of the future:

|

| Figure 3: Survey respondents’ wishes for future digital museum resources. |

This time the responses were far more positive, with “straightforward” and “accessible” clear winners, and there were a greater variety of themes with 91 different words represented in Figure 3, compared with 55 in Figure 2. Generally, each respondent had more to say here as well, with the total frequency of words for the aspirational set reaching 236, and 151 in the responses for current provision. This may indicate that despite the slightly negative view of digital resources so far, there is still an appetite for and openness to the idea of future developments in this area.

Technical requirements

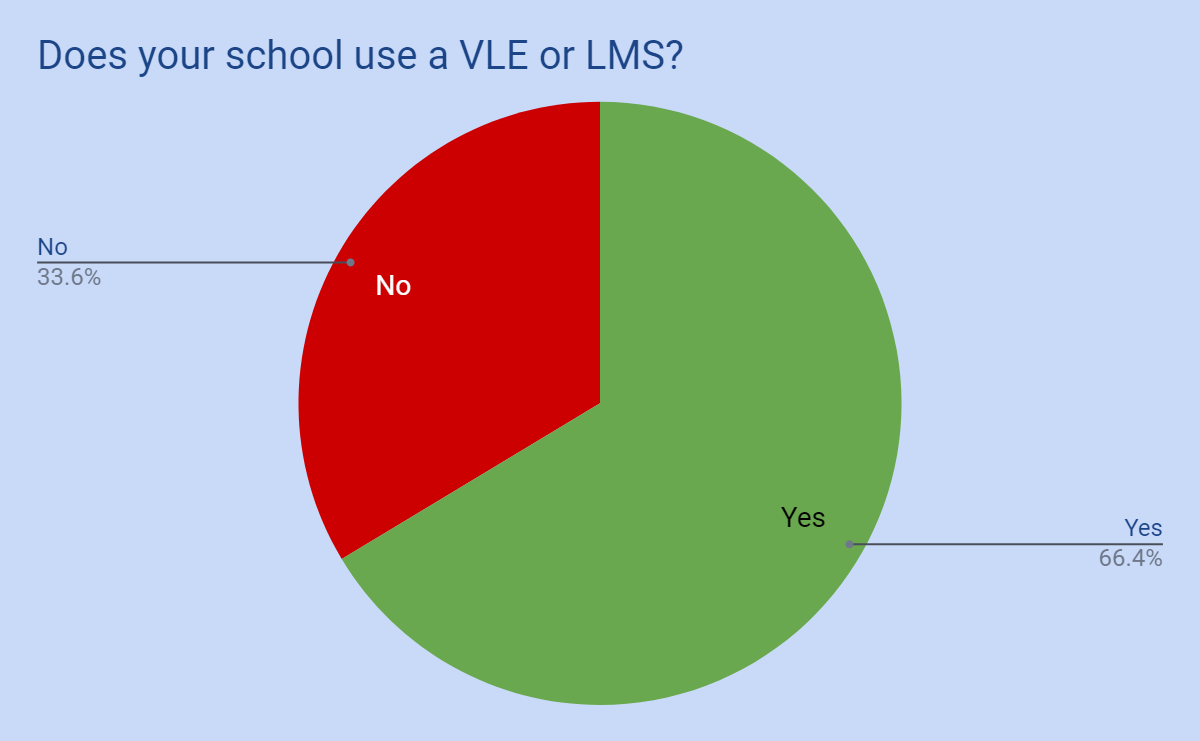

From informal conversations with school teachers, as well as regularly visiting schools around the country, it appears that most now use some form of Virtual Learning Environment (VLE) or Learning Management System (LMS). These two forms of technology do have subtle differences but for the purposes of this assignment they will be treated as equivalent and may be used interchangeably. It is not immediately obvious how important integration with these systems may be for digital resources obtained outside schools, so some of the questions in the survey were designed to clarify this.

|

| Figure 4: Pie chart - Does your school use a VLE or LMS? |

|

| Figure 5: Pie chart - Are any of your resources integrated via SCORM or LTI? |

Figure 4 shows that roughly two thirds of respondents’ schools use a VLE or LMS, but figure 5 illustrates that almost 70% of those in this group do not know whether any of their resources are integrated via SCORM or LTI. These are two common standards for technologies that integrate digital resources into educational systems so that (for example) results of quizzes within a resource can be recorded against a learner’s account within the VLE. Most teachers spoken to informally were responsible for choosing and implementing the resources they use in the classroom, so the fact that so many do not know about SCORM and LTI integration implies that these are not widely used by classroom teachers.

|

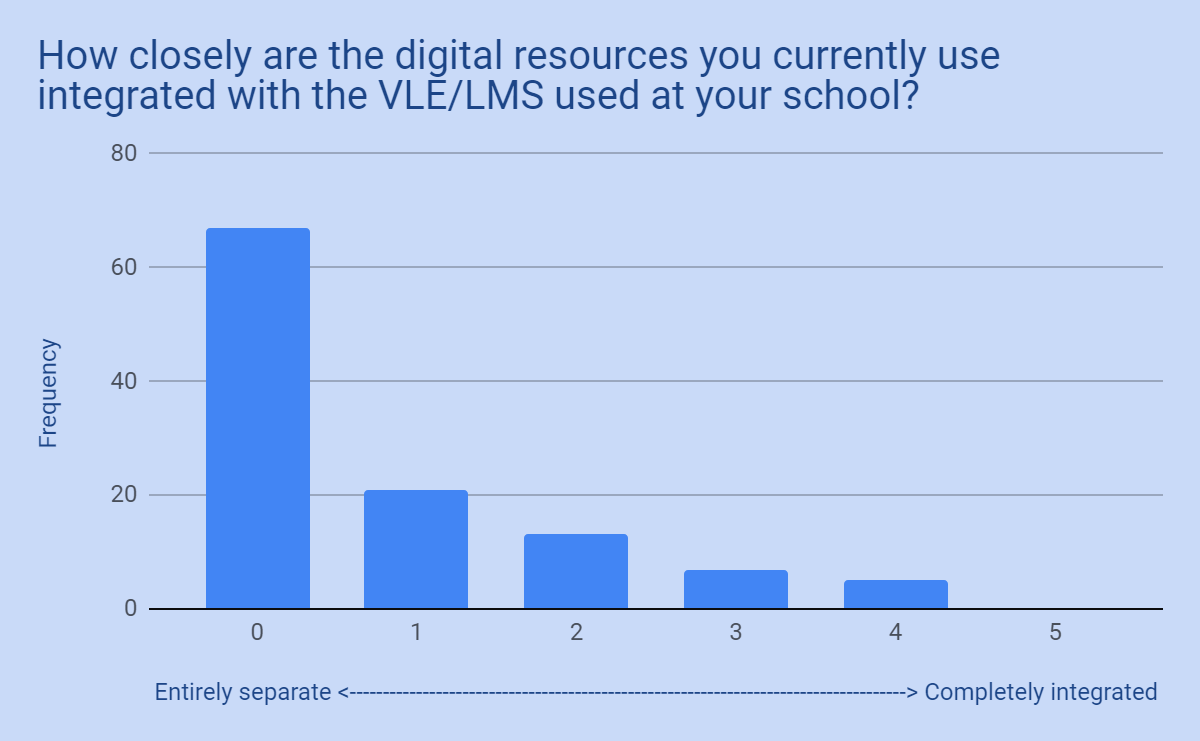

| Figure 6: Bar chart - How closely are the digital resources you currently use integrated with the VLE/LMS used at your school? |

Figure 6 corroborates that, with most respondents stating that the digital resources that they currently use are entirely separate from their school’s VLE, and nobody stating that they are completely integrated. These results all suggest that VLE integration is not important (to teachers) for the time being.

In Figure 7 it can be seen that respondents were overwhelmingly geared towards resources that could be used on a laptop or desktop computer, with relatively few looking for something to use on mobile devices. This may indicate that a majority of the teachers are expecting something that can be presented to learners rather than interacted with directly by learners. The surprising number who chose “print onto paper” may be related to the observation earlier that most digital resources encountered in the initial research were printable pdfs.

|

| Figure 7: Bar chart - How would you prefer to use digital resources? |

Resource features

School teachers have a large amount of subject matter to cover in a relatively short amount of time so it seems clear that any resources produced by museums must contribute to this in some way. Figure 8 supports this idea, but suggests that links to taught curricula may not need to be completely explicit. Figure 9 may go some way to explaining this as cross-curricular links are ascribed some importance in these data.

|

| Figure 8: Bar chart - How closely must a digital resource be linked to an aspect of the taught mathematics curriculum? |

|

| Figure 9: Bar chart - How important is it to you that a digital resource from a museum shows links with the curricula of other subjects? |

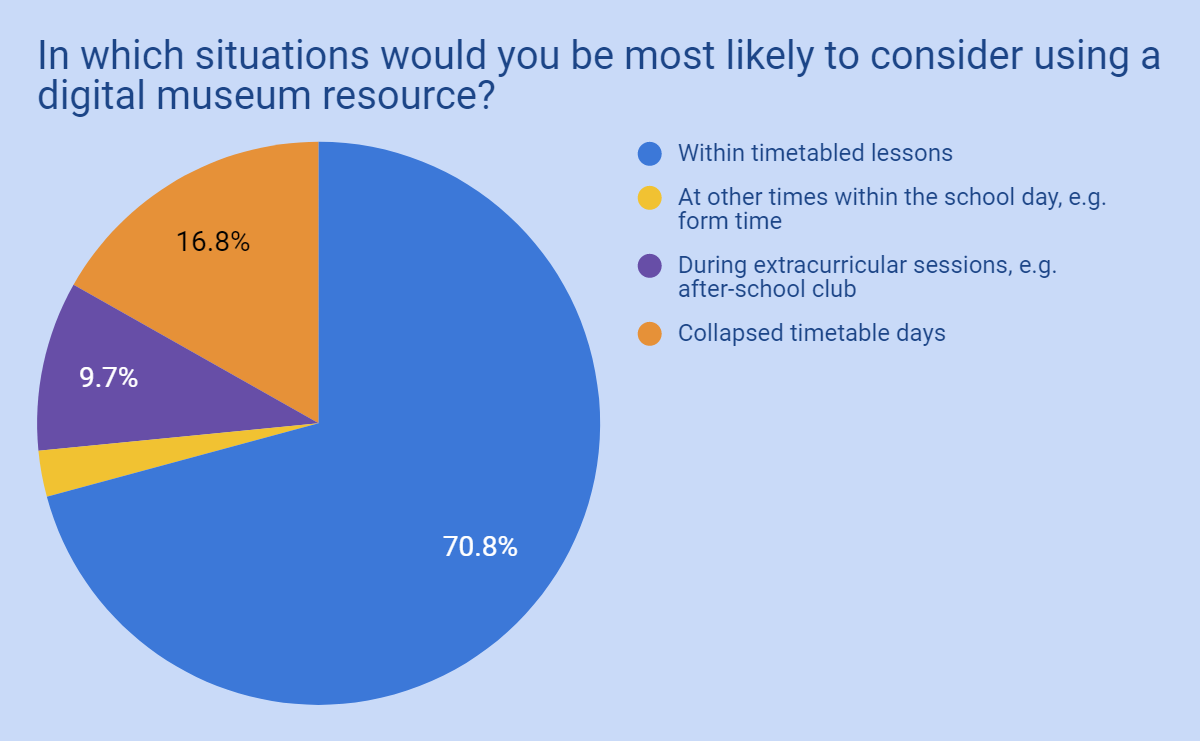

In terms of the focus and scope of resources a large majority of respondents indicated a preference for lesson-based activities, although a little more than a quarter expressed an interest in resources intended for use at other times (Figure 10).

|

| Figure 10: Pie chart - In which situations would you be most likely to consider using a digital museum resource? |

It can be seen in Figure 11 that short activities lasting a few minutes would generally be preferred, but that there is also an appetite for resources suitable in a range of situations.

|

| Figure 11: Stacked bar chart - Please rank the following digital resource types in order of preference. |

Conclusions

From the research detailed above it appears that there is certainly a place for digital resources produced by museums in the mathematics classroom, but this research makes it clear that to be successful they must be planned and designed appropriately. Bringing together Lin, Fernández and Gregor (2010) with the findings from the teacher survey they must be novel yet accessible and straightforward; multisensory and story-based yet fit within a tight educational structure restricted by short timescales. They must also be curriculum-linked, but with some flexibility; the opportunity to explore cross-curricular links as well as introducing students to extracurricular “real world” and historical uses of mathematics is of great value and something which museums are uniquely placed to exploit. This harks back to Martin (2004)’s “straddle the ‘formal’ and ‘informal’.” Some of the survey responses indicate that a breadth of resources are what is called for, which may be difficult given budgetary and other constraints that museums are subject to.

The research findings also prompt further questions, such as:

- The expectation from teachers appears to be for resources explicitly delivered by teachers rather than experienced independently by students. Is this what teachers genuinely want, or is it what museums have taught them to expect?

- There is currently a lack of interest in VLE integrated resources, but is this something that will change as more schools adopt their use and more teachers gain experience?

This topic represents an interesting opportunity to explore a direction that isn’t the subject of much prior research. Further study is evidently required which, although fairly niche, has the potential to prompt positive change and development in two disciplines that are often thought of as being quite distinct.

References

De Freitas, E. and Bentley, S.J., 2012. Material encounters with mathematics: The case for museum based cross-curricular integration.

International Journal of Educational Research, 55, pp.36-47.

Harrell, M.H. and Kotecki, E., 2015. The Flipped Museum: Leveraging Technology to Deepen Learning.

Journal of Museum Education, 40(2), pp.119-130.

Jisc, 2018. Fourth Industrial Revolution inquiry. [pdf] Jisc. Available at: <http://repository.jisc.ac.uk/7152/1/fourth_industrial_revolution_inquiry_.pdf> [Accessed 15 August 2019].

Lin, A., Fernandez, W. & Gregor, S. (2010). Designing for enjoyment and informal

YouTube as the art commons?

407

learning: a study in a museum context.

Proceedings of the 14th International Pacific Asia

Conference on Information Systems (

PACIS 2010), 904-915.

Martin, L.M., 2004. An emerging research framework for studying informal learning and schools.

Science Education, 88(S1), pp.S71-S82.

National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, 2015. Strategic Use of Technology in Teaching and Learning Mathematics A Position of the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. [pdf] NCTM Available at <http://www.nctm.org/Standards-andPositions/Position-Statements/Strategic-Use-of-Technology-inTeaching-and-Learning-Mathematics/> [Accessed 16 August 2019].

Parry, R., Eikhof, D.R., Barnes, S.A. and Kispeter, E., 2018. Mapping the Museum Digital Skills Ecosystem-Phase One Report.

Rowlett, P.J., 2013. Developing a healthy scepticism about technology in mathematics teaching.

Journal of Humanistic Mathematics, 3(1), pp.136-149.

Welsh Government, 2018. Digital Competence Framework Guide. [pdf] Welsh Government. Available at: <https://s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/hwb-live-storage/6e/7f/33/19/c3494e069deaeab755d4c156/digital-competence-framework-guidance-2018.pdf> [Accessed 16 August 2019].

.jpg)